I’ve been home for 14 days from this last trip west and have been sitting on this post, struggling to focus due to the global state of despair in the air. Today, after a long, crisp fall walk and the election and work week looming ahead, I feel determined to push through my brain fog to keep up my goal of continued sharing. I also feel motivated by Marte Harter's spirit. More on her shortly, but first, a little back story. My folks moved to Washington state in 1989; for me, it was the summer between 5th and 6th grade. I don’t remember exactly the first time we went to Orcas Island, but now I’ve been going there fairly consistently when I visit for the past 30 years. My mom still goes regularly, and when I stay with her, we often make the trip together—packing food for a few-day adventure. She’s got a spot she loves, cabins right on the water with a kitchenette, and is dog-friendly, which up until recently was a must for her sidekick Charlie (RIP). You can see the sunset and feel like you are on the edge of the world.

Without getting too lost in describing the magic of the San Juan Islands, an archipelago between Washington and Vancouver, B.C., just trust me; they are incredible. If you’ve never been and get the opportunity, get onto that ferry and let the salty mist envelope you. After the ferry docks on the island, I usually end up in Eastsound getting a coffee, going to the local bookstore cause I can’t help it (hot travel tip: the public library in town also has an excellent used book shop), and picking up anything forgotten to make meals or necessary snacks at the small pricey (island life) food coop. There are also a ton of small souvenir shops, spots to buy local art, and some decent restaurants. Eastsound is also where the Orcas Island Historical Museum is, a place I’ve walked past dozens of times but never gone into for this reason or that.

The display at the museum about Marte Harter is pretty small, and my photos don’t do it any justice. I wasn’t expecting to get sucked into her story, and these were meant to be a reference point, perhaps to google later or circle back to, a habit I have for myself since my memory recall isn’t great. Her story drew me in because since I was a kid, I’ve been interested in women who were doing things that pushed gendered boundaries. I didn’t read everything in detail, but Harter’s story of coming to the island in the 1940s and building a cabin with her friend Tony piqued my interest since I have a lot of friends who have moved off the grid to build their own homes and, in a past life, spent extended time in some of them.

If time affords it, I really like reading about the history of a place while in it. It helps me to think critically about how history is told and how it can be told better or differently. I wasn’t expecting to be drawn into Harter’s book Cabin on the Island like I was; now, 3 weeks later, I’ve been sucked into her life, trying to lace together a few bits of her story that I’ve been able to collect. I imagine this won’t be the end of my thinking about her. Written in first person, Cabin on the Island was published 2022 posthumously by Harter's nephew, S. Sëan Tretheway. The book's dedication reads In Loving Memory of Marte Harter. Writer, Pioneer, Conservationist, Artist, Islander. December 10, 1921 - October 8, 1999. In his brief but poignant foreword, Tretheway notes that he found the manuscript his aunt wrote in his mother's papers after she passed away and was inspired by the story. “It is my pleasure to honor my aunt by publishing this wonderful account of her first years on the island when she and her partner, Tony Howard, built and settled into a cabin. This is a love story of two women’s undeniable strength and will to survive in the wilderness.” He also appropriately signs off with an acknowledgment to “the original inhabitants of this island - The Lummi Nation - their ancestors, present elders, and future generations.”

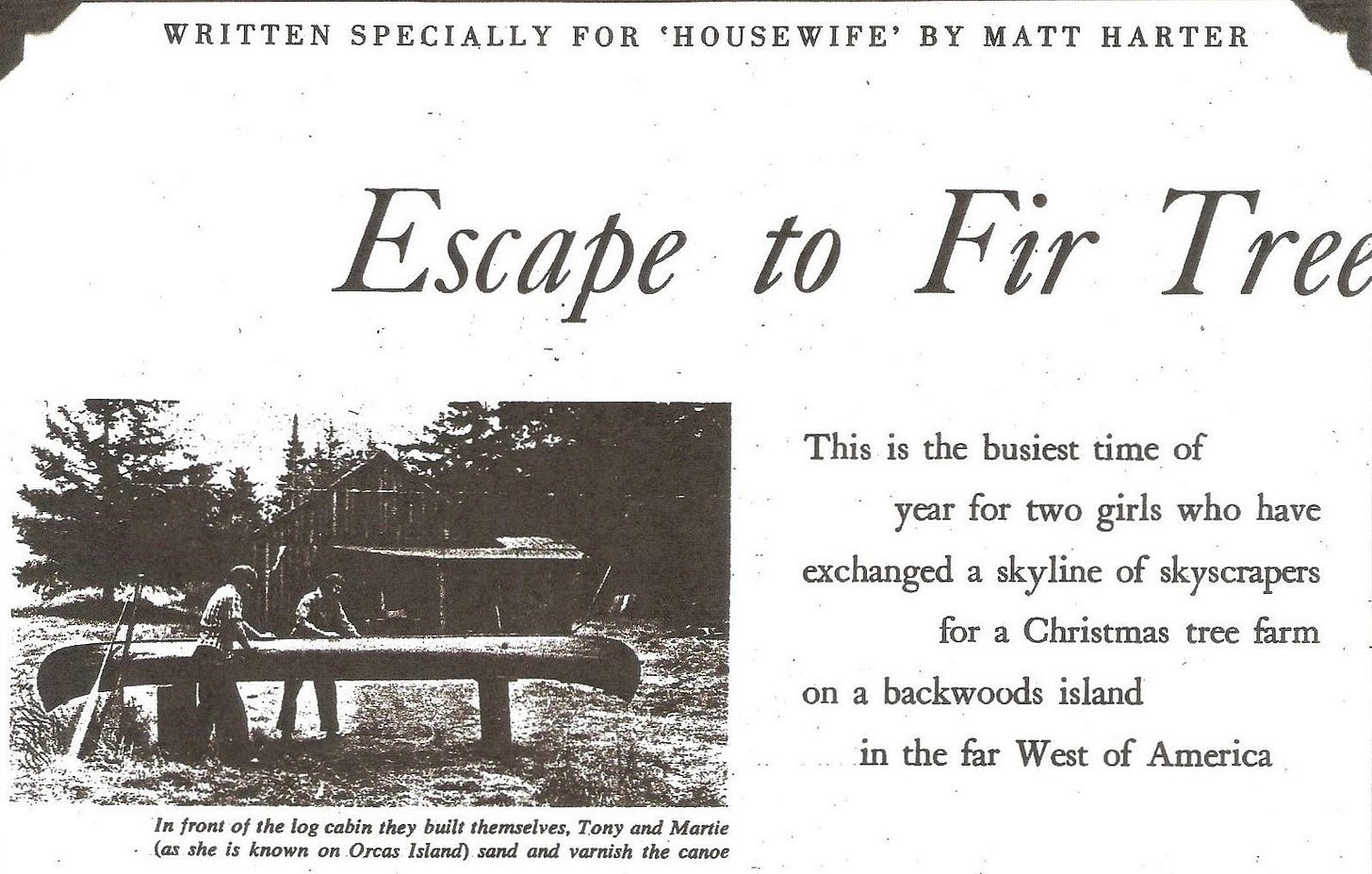

My mom and I were on the island for 2 nights; I finished the book a few days later while on the bus to the airport and wrote Tretheway an email from my phone at the airport to say thank you and see if he had any additional photos of Marte and Tony together. Funny side note: I was a little rushed at the museum because my mom was waiting for me, but I didn’t realize Harter’s partner Tony was a woman when I bought the book. So, just roll with that, but obviously, I was thrilled. I also reached out to the museum to see if they would send any other images and, in particular, a readable copy of the photocopied article on the table, “Escape to Fir Tree…” from HOUSEWIFE by Matt Harter (see the yellow circle on the image above.) I did some light googling for Matt Harter, assuming it was a relative, and Housewife magazine, but found nothing.

I was pleasantly surprised that both Tretheway and Michelle Hassebrock, the Program Administrator of the Orcas Island Historical Museum, wrote back to me within the week. Both sent photos, and Hassebrock enlightened me with some information, sharing that “Marte's given name was Martha, and she went by several different names/spellings in her life, including Matt. In fact, even the "Fir Tree Island" that she writes about in the article is actually Orcas Island!” Okay, so Marte used a gendered pen name, Matt, noted. Hassebrock also shared that the photocopy of the article (that she included a copy of in the email) was from a photocopy from the family’s records, and hasn’t been able to find an original or better copy. She dates the piece between 1952 and 1955 based on Harter’s life, so if anyone reading has access to a copy of HOUSEWIFE from that time, flip through to see if you have the golden ticket. She also included a few photos (some that Tretheway also shared in his email) and a 1953 Seattle Times article that, according to Hassebrock, Tony and Marte were displeased about how they were represented. Hassebrock pointed out that Marte isn’t in the photographs from the Times piece, but apparently, she was the photographer.

Cabin on the Island highlights a type of willingness. I think you typically only have, in your 20s, to go into an entirely unknown situation. I was drawn into Harter’s narration of how she and Tony decided to leave their office jobs and stay on the island and her honesty about their failure and successes. They name their cars. They have a cat named Lavender. The story of building their house is woven into survival. Forging and hunting for food (so much mushroom hunting) and lots of stories about their jobs working in various fire towers (it was pointed out to me at lunch Friday by a friend that many beat poets worked fire lookouts in the region and likely during this period, so I’m putting a pin in that for later) and their seasonal business selling Christmas trees (the focus of The Seattle Times article). One of the two is quoted in an article saying, “We can live on very little money on the island because we don’t need money except for things like petrol, flour, and coffee.” I appreciate Harter's humbleness throughout the writing regarding the learning curve around existing in a wild place, understanding the interconnectedness of the flow of seasons, and respecting nature. Her reflection on the impact of tourism is way ahead of its time and so inspiring. Community building is, at the book's core, a reminder that survival can rely on helping one another, something we’ve witnessed in the past weeks in Western North Carolina.

Years ago, I used to spend weeks living off the grid at my friend's land project in the Smokey Mountains of Western North Carolina (fundraising shout out to their mutual aid mentioned above). I would call the days and weeks that blurred together “sticky mountain time.” Harter had a similar sentiment when she said, “Here time was so endless as to be non-existent. Here, because there was no time, There was time for anything. My life belonged to me. And having this much, I wanted to keep it; I wouldn’t willingly go back.” I enjoyed this book, and a big part of my appreciation for it is the larger story beyond the book and how many questions I have. How it feels like Marte, Tony, and the friends in Seattle they talk about (Gerry and her houseboat!), who I’ve obviously imagined are part of a larger potentially queer network, could be my friends in a past life. I am so grateful that her nephew saw value in sharing the story she wrote, and the Orcas Island Historical Museum stewards her papers and was generous enough to give permission for me to include them in this post. Cabin in the Woods is available online here.

PS: A tip of the hat to Kate Millett and her Christmas tree farm.

I also grew up going to Orcas Island and have never encountered their historical society - what a special place! You have such a knack for finding and sharing stories. I want to read Cabin on the Island!

So good Faythe! They named their cars! So many good details here :)