I want to rise and push everything up as I go.

Spending Labor Day in Silver City, New Mexico

I am stepping into week two of a residency hosted by Power and Light Press in Silver City, NM. I came here specifically to do family genealogy research rooted in the 19th century. Of course, I’m listening and learning as much as possible about the area while here since part of traveling for me has always been learning in place, and history is all connected. Before I came, I made appointments with several cultural institutions for research, including the Silver City Museum, J. Cloyd Miller Library and Fleming Hall Museum at Western New Mexico University, and the Luna County Historical Society Museum and Archive. The Silver City County Clerk’s Office and the local cemetery welcomed me with no appointment, providing very different types of valuable information.

I’ll spend most of my time at the Silver City Library this week, working with their local history collection. Every librarian, archivist, museum, and city worker I’ve met with has been incredibly generous with their time, answering my obscure questions, making time to pull papers, showing me how to use their collections best, and sharing their local history knowledge. Thank you, Ashley Smith, Andrea Jaquez, Debra French, Ken Dayer, and the women at the County Clerk’s Office whose names I didn’t get. I’ve been in more back rooms and collections this week than in years, and I feel inspired, overwhelmed, and grateful to have this time to learn and lift stories out of stacks. I am also, as always, finding it difficult to stay focused.

This morning, I took a short drive from Silver City to visit the active Santa Rita Copper Mines and the Historical Markers nearby, which I learned about from the New Mexico Historical Women Marker Program. I was motivated for a few reasons; when I came to Silver City, I knew there was a history of extraction and displacement brought by colonizers, but nothing about the 1950 15-month-long miners’ strike history or much about the blacklisted movie Salt of the Earth (1954), based on its radical story and filmed in the area. So much has been written about both; if you are curious, I recommend this 2023 article, “What an Epic Women’s Strike Can Teach Us Over 70 Years Later: The 1951 Empire Zinc Strike made history and spawned a landmark labor film. Its impact is still reverberating today.”

“I remember we pulled the hood up on one car and put sugar in the gas tank,” Torrez later told the Santa Fe New Mexican. “We also used knitting needles” (as weapons).

At the Silver City Museum, I learned that many of the film’s actors were local folks who participated in the union organizing and the picket line. After digging around a bit online, I found this excellent resource for reflection: the Salt of the Earth Recovery Project, which connects oral histories by folks from the local communities to the combination of their relationship to the mining industry, the strike, and the film and its impact on their lives.

This website examines how Salt of the Earth complicated common stereotypes of Mexican-origin peoples in a Cold War political environment and American popular culture. With bracero worker agreements under increased scrutiny and U.S.-Mexico repatriation efforts in full force through paramilitary operatives such as “Operation Wetback,” Salt of the Earth humanized mexicano laborers, exposed exploitive work conditions, interrogated environmental impact of the mining industry, and challenged the local political structure.

On the Recovery Project site, community member Marivel J. Medel talks about the Union Hall mural I had pulled over to photograph one day: “The Mural on the hall is some of the only art in public places in Bayard. As a whole it’s a representation of our people and history. It is a part of our background, childhoods, and history both in a figurative sense and a literal sense.” Rachel Juarez Valencia, now a community elder who was 14 at the time of the strikes, remembers, “Years later after retiring from teaching, I started substituting at Cobre High School in Bayard and some juniors in the art class asked me for permission to leave the school to go and do a painting somewhere in the community….Years later, I found out that the painting they did was done on the outside of the Union Hall wall and it was a mural of the women picketers of the Empire Zinc Strike in Hanover, New Mexico, which included me.”

Last week, at the volunteer-run Luna County Historical Society Archive, I was given free rein to dig around as long as I put things back. This place epitomizes why community archives are so important (and always need support). There were stacks of unprocessed (meaning it’s difficult to know what there is and where it might be) invaluable documents donated by community members, including many photo albums and scrapbooks. I’m always drawn to other people’s obsessive collections, and scrapbooks are gold mines for deep dives (this also led me to buy a copy of Scrapbooks: An American History, Yale University Press; 2008). Whoever made this book had saved and clipped two years of articles from various regional papers focusing on the Union’s strike, meticulously laid out and pasted in. It’s impossible to say the last time, if ever, this object had been handled. I felt honored to find it and spend a little time with its contents and history.

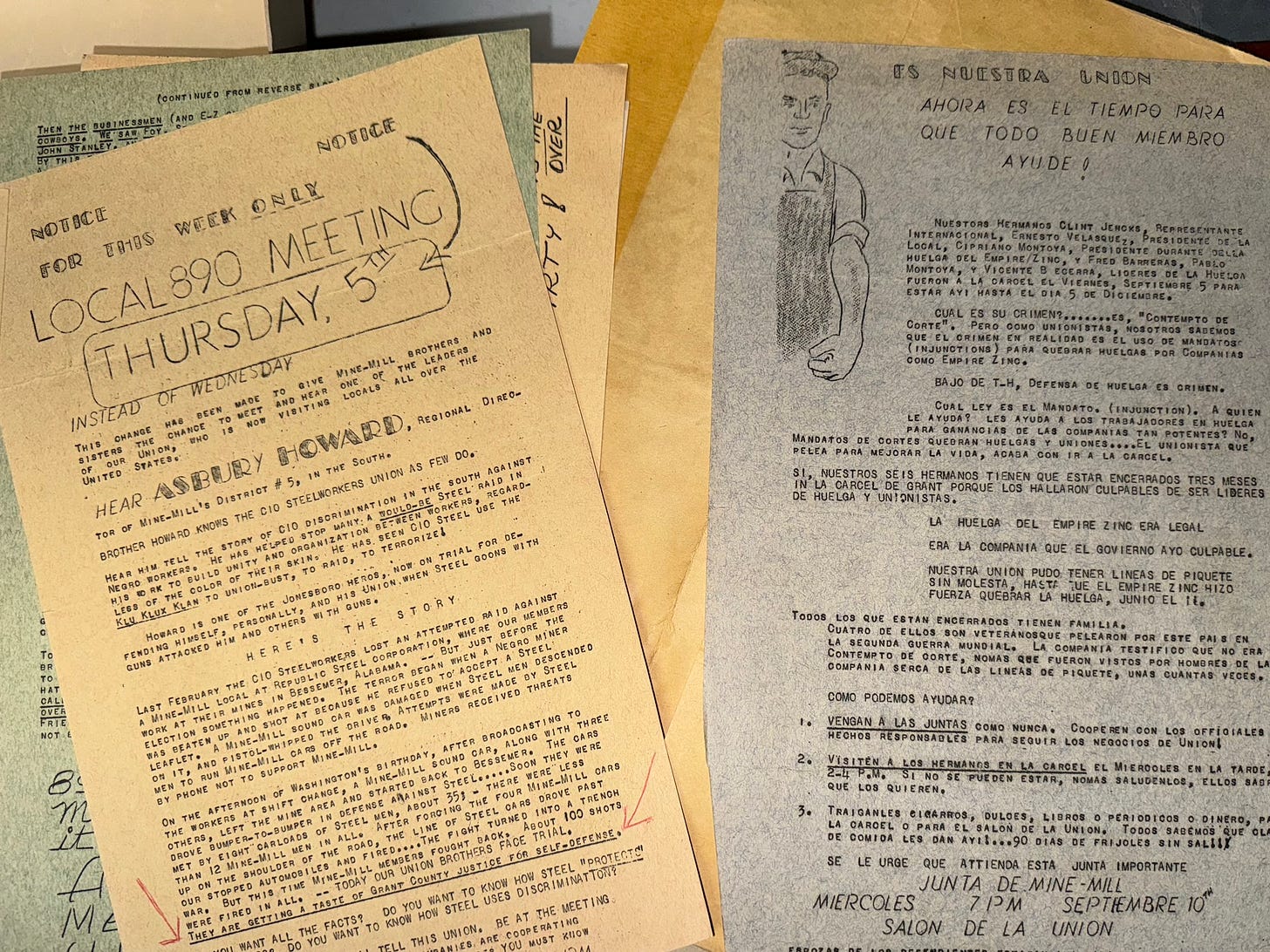

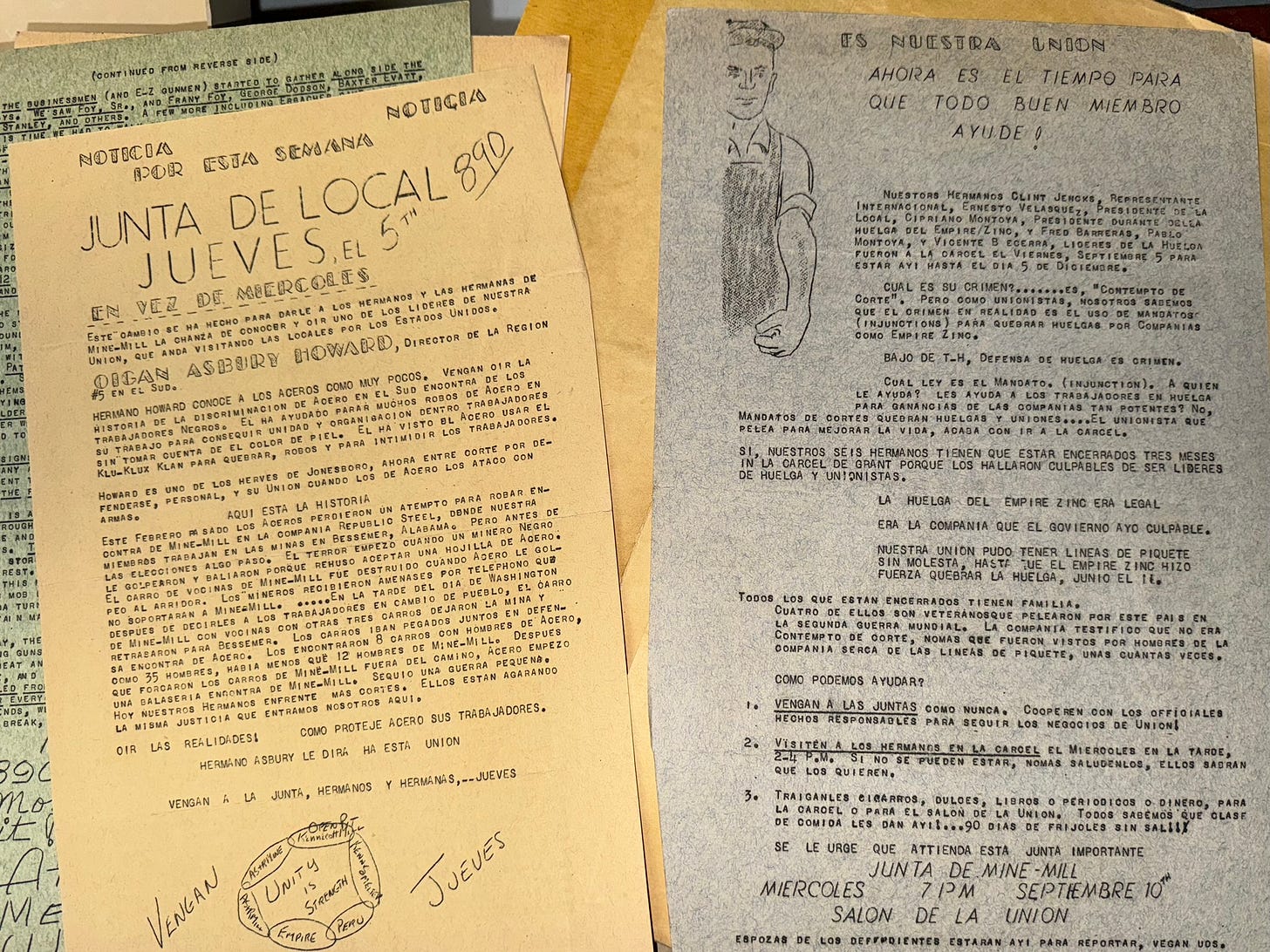

Another surprise came at the end: tucked in the back of the scrapbook was an envelope containing about 20 mimeographed Local 890 newsletters. Most were double-sided and in both Spanish and English. I photographed most of them, so feel free to reach out if these speak to you. I’m happy to pass images along.

I need to get on with my day, so I’ll wrap it up here trying to bring it full circle. While watching the film based on a real-life event, I couldn’t help but place these real-life union newsletters into this scene from the movie.

From the PDF of the movie script, the dialog from this scene;

ESPERANZA'S VOICE

Letters came. From our own people, the Spanish-speaking people of the Southwest ... and from far away -- Butte, Chicago, Birmingham, New York -- messages of solidarity and the crumpled dollar bills of working men.

CAMERA PULLS BACK SLOWLY TO DISCLOSE

two women at a mimeograph machine.

CAMERA PANS SLOWLY AROUND

the union hall, disclosing other women at work -- cutting stencils, filing papers, sealing envelopes, etc. Several small children romp and climb over the benches.

ESPERANZA'S VOICE

But that was not all -- we women were helping. And not just as cooks and coffee makers. A few of the men made jokes about it, but the work had to be done -- so they let us stay.

MEDIUM SHOT, FEATURING ESPERANZA

standing behind a desk, sealing envelopes. The infant Juanito lies on an improvised pallet beside her, hemmed in by piles of leaflets. Estella is licking stamps.

Read more about the film in this 2022 review, “Salt Of The Earth – The Power Of Women’s Solidarity In The Empire Zinc Strike.” And if you want to go deep, historian Ellen Baker “examines the building of a leftist union that linked class justice to ethnic equality” in her 2007 book On Strike and on Film: Mexican American Families and Blacklisted Filmmakers in Cold War America.”

(53:48) ESPERANZA'S VOICE

By sun-up there were a hundred on the line. And they kept coming--women we had never seen before, women who had nothing to do with the strike. Somehow they heard about a women's picket line -- and they came.

Let us embody the narrator Esperanza, who says towards the end of the film, “I want to rise and push everything up as I go.”

Love love love this. Wish I was there with you!