PARANOIA? Wait until you see the ceiling!

A shallow dive into the Village Voice Bulletin Boards of the 1960s and the First International Psychedelic Exposition.

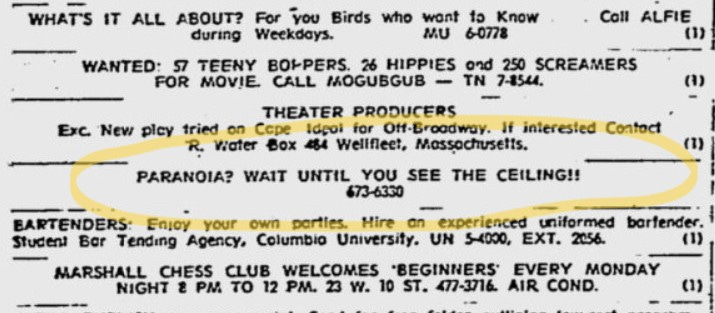

“We put ads in the Village Voice and the bulletin board section following our progress: Paranoia, Wait Until You See the Ceiling. Paranoia, What Do You Think It Means? Stuff like that.” -Merril Mushroom, interview with author 2016

I’ve been sitting on this post pushing towards a month. I couldn’t seem to wrap it up. Get it finished. Hit send. I know my inability to get it done is because I feel stunted by the daily dumpster fire of news and falling down the slippery slope of why talk about anything not hyper-politicized right now when everything is so hyper-politicized. Well, here I go. And, I guess most things I write aren’t not political; there’s more radial history here than I initially realized when I started this post three weeks ago by saying, “Sometimes, when I can’t sleep and know I can’t do anything focused, I look at old digitized magazines and newspapers.” So, I’ll keep rolling with that draft and get this out into the world, even if it’s just for the sake of my mental health of moving forward. It’s gonna take me a minute to tell you about that perfect mustachioed side eye Paranoia business card, but maybe stick with me for the ride; it’s a winding story about some gays who had a short-lived headshop in 1967 (or 1966, depending on the account).

Talking to the void until it resonates with someone is good therapy for me; I’ve been doing this my entire life, whether it’s via a zine, Myspace, Blogspot, Facebook, IG, or Substack in 2025. If I were around in the 1960s, it probably would have been in a local newspaper or hyper-local newsletter. Over the past few months, I have spent a lot of time flipping through digitized issues of the Village Voice. Usually, I’ll randomly pick an issue. There is almost always something, an article, ad, or review, that sets me off into a spiral of wanting more information.

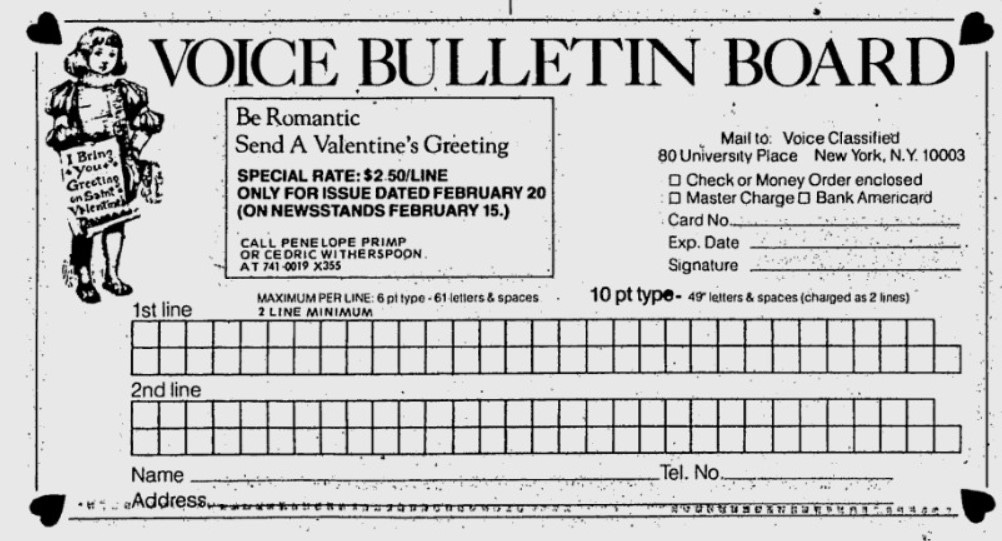

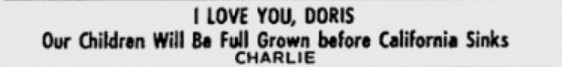

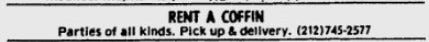

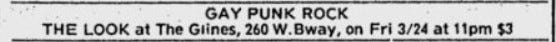

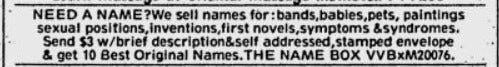

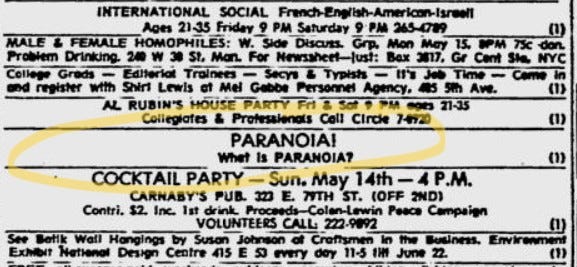

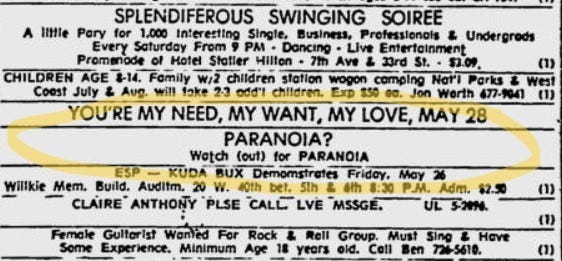

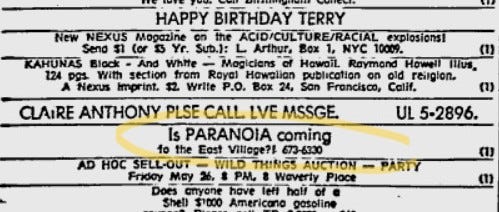

Then, A few weeks ago (edit: well, now this particular story was over a month ago), I started honing in on just the “Bulletin Board” section on page 2 of each issue beginning in the 60s. The Bulletin Board format is a single page (or less in the earlier versions) at the front of each issue of the weekly paper and, in the late 1960s, began to take up more space and connect with the classifieds in the back where you find your typical listings of jobs, apartments, legal postings, things that you would still see in a regional printed paper. I started thinking about that space as a living archive of so many unedited voices: tourism, religious groups, concerned parents trying to find their missing kids, business owners, hustlers, SWs, romantic and birthday shoutouts, pyramid schemes, club owners, authors, and musicians promoting events, early queer and anti-government organizing; it’s all tucked in there with the word count of a tweet. Typically, each message is evident in purpose and has a straightforward point. Less frequently, there are mysterious, coded, and vague posts that are maybe just talking about something so dated it’s lost in translation of time and the flat-out obscure anonymous posts. After some time, I locked into a series of stylized and coded messages that started having me methodically going through issues, looking for patterns and any information or clues about who or what they were. They are strange and interesting, and I’ve spent too many late hours trying to crack some likely nonexistent code. But I’ll return to this in a future post, even if I can’t figure anything out. For now, here are some random favorites I saved.

Okay, so you get the idea. It’s all over the place, and I’m addicted. Some other notable highlights I stumbled across in various issues were a post for the LESBIAN switchboard, Valerie Solanas promoting her SCUM (Society for Cutting Up Men) Manifesto, and an ad to “Groove with James Baldwin & Richie Havens at the Village Theater” for their benefit performance “No One Heard the Poet” performed for the first time. I went down a wormhole about that one; all proceeds went towards the Harlem Six and the Black people of Dorchester County, SC. The next issue from August of 1967 reported, “Baldwin’s prescription for the fires this time was the same as last time: massive economic boycott.”

Then, things got weird when I stumbled across a tiny blip of a post, more on the cryptic side, in a 1967 Bulletin Board that triggered a memory from an interview I did ten years ago. I had to check the math twice because I could hardly believe it had been that long since I lived in rural middle Tennessee. This was a time of healing and coming into myself. It was a time full of intentional rest after some major burnout from making two films, touring, and working service industry jobs simultaneously full-time. I was stubbornly proud about burning the candle at both ends, but my reality of being a “successful” working artist had backfired in many ways, and I had to force myself to slow down. Through a chain of events involving a significant romance, I moved into a small rented cabin where my closest neighbor was a mile away. It was a complicated magical time with an expansive radical queer community at my fingertips. The rural gayborhood in this area has roots in the 1960s back to the land movement and has since morphed into the wildness of what it is today, tucked between nooks and crannies of hollers and hills, spread out over a wide circumference thriving on its many ever-changing terms (I haven’t been back in over five years, so this is based on my personal experience and memories). It was there I met my friend Merril Mushroom.

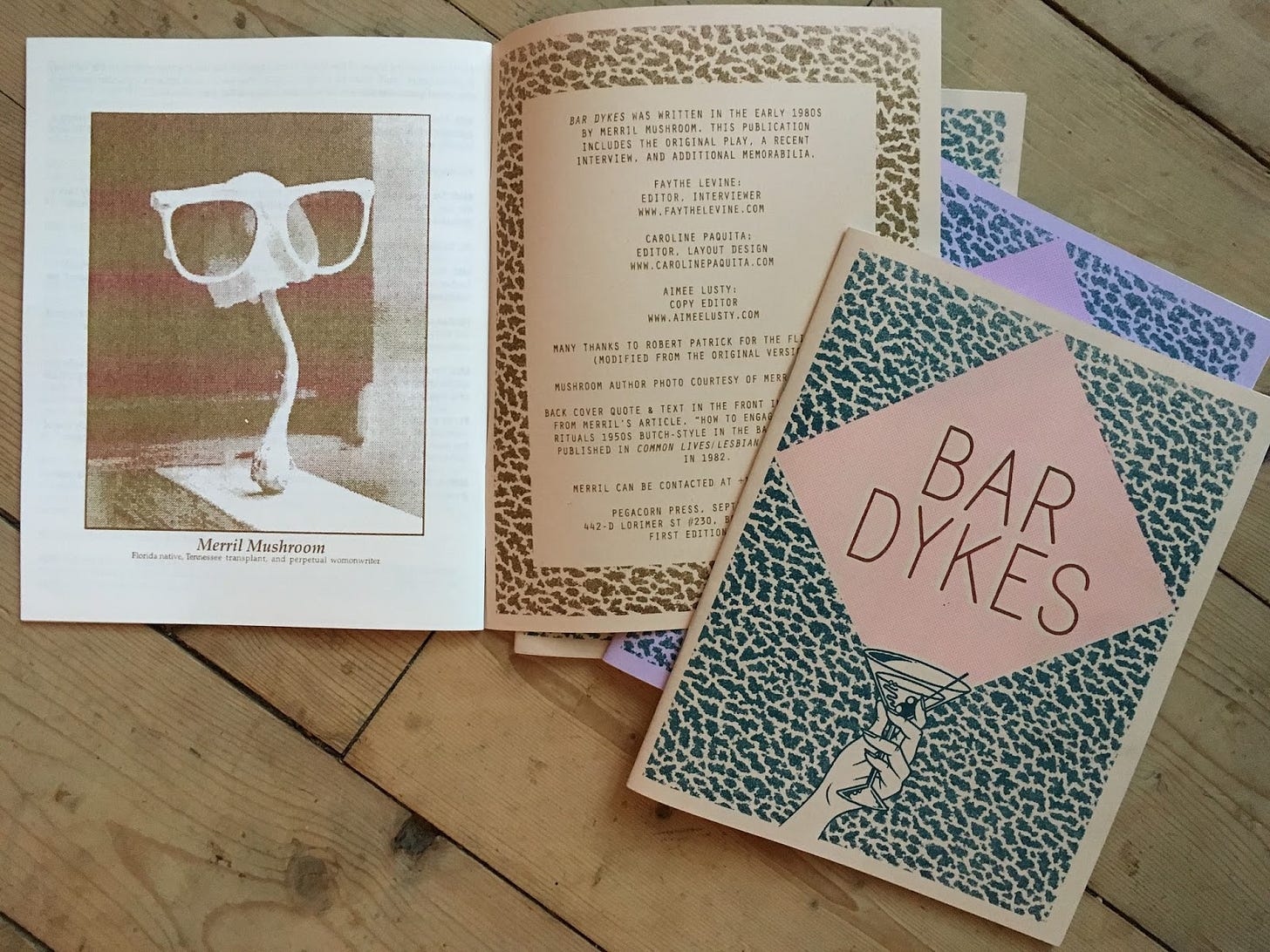

It was 2016; Merril was 74, two years younger than my parents, living with indoor plumbing for the first time in over 30 years after her home with all her belongings had recently burned. The house fire consumed Merril’s archive of her expansive writing, books, memories, and most of her family photos. Her beloved Lesbian community of 50 years began to send things back to her to fill her new home with memories, including a lightly annotated photocopy of her play Bar Dykes. If you are curious, there is a lot of information about Merril: oral histories, interviews, and, of course, my reissue of the play with her interview, which she was gracious enough to work on with me. All to say, dig around; she is inspiring, to say the least. She was my first elder queer friend, and we hung out a lot while I lived there.

Merril wrote the play as a young butch in the 80s about 1950s lesbian bar culture. To my surprise, at the time, it had only been performed twice since. In our interview, Merril explained, “Bar Dykes started with the article, “How to Engage in Courting Rituals 1950s Butch-Style in the Bar,” that I wrote for Common Lives/Lesbian Lives Magazine. We used to perform the Courting Rituals piece as a play from time to time, acted out with just a few people. Then I was talking to somebody about bar herstory in New York and thought it would make a good play. Courting Rituals came out in the early ‘80s, then Bar Dykes came out of that. It was performed in ’84 and again in ’92.”

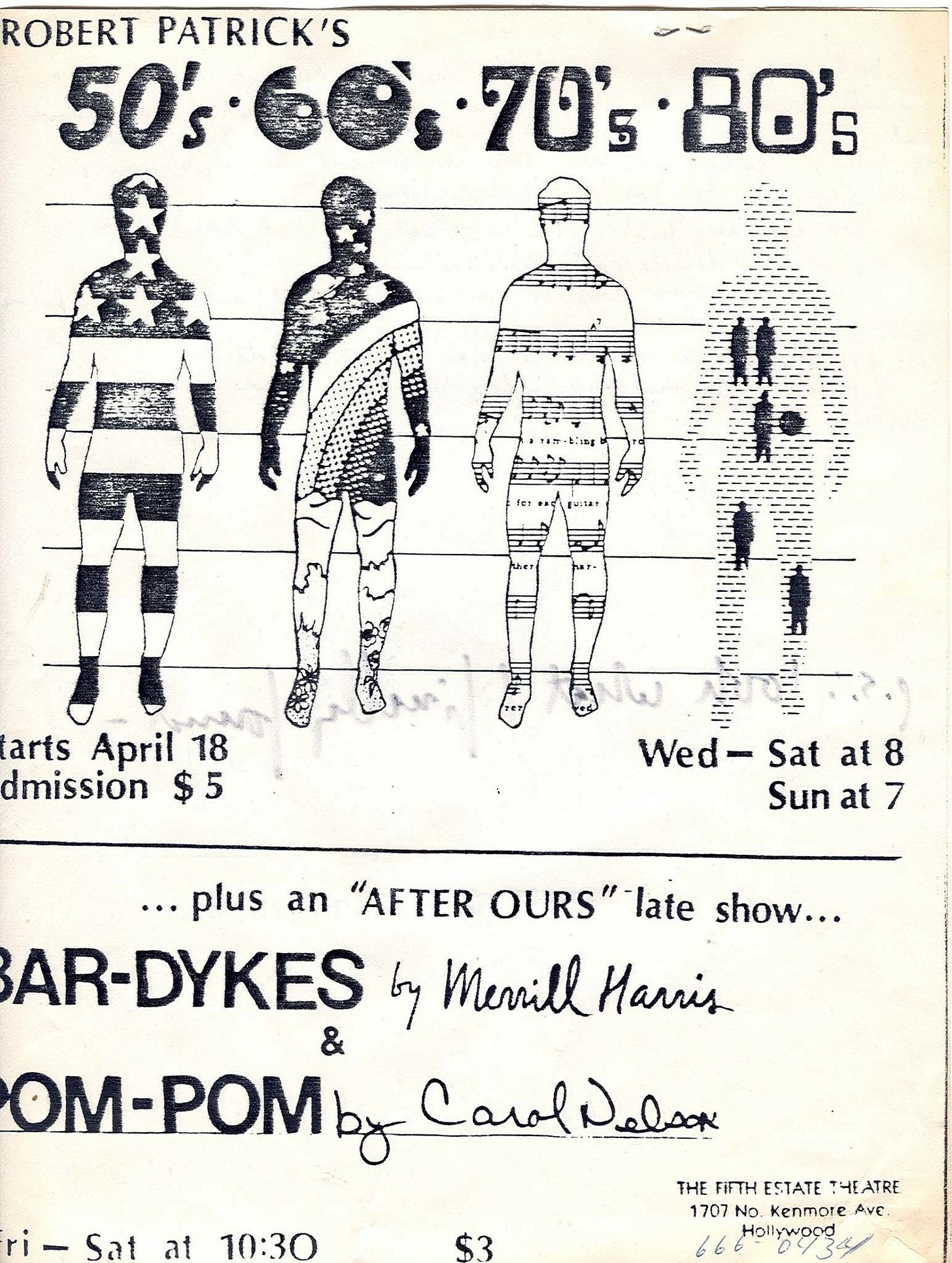

I had reached out to director Robert Patrick around this time, Merril’s old friend from New York, who has since passed away. He was super friendly when I emailed him to see if he remembered the production. He quickly responded with the flyer from the 1984 production he produced and then, months later, a very grainy newspaper reproduction of that cast from his archive that I had forgotten about until I searched his name in my inbox. I haven’t had the opportunity to share it until now.

I knew this work and Merril’s story would have a larger audience. Merril agreed to let me record us talking about her life story, with the intention that it would be transcribed, edited, and included with a publication of the play as it existed. Over a two-hour tea date with a smoke break, Merril generously shared her life story with me. The rambling interview is riddled with me asking one million questions; here’s a previously unpublished example for some context:

Merril Mushroom: I came out at the end of high school. I came out to my mom a year after that.

Faythe: Did you start going to gay bars in high school or did you wait till you’re in college?

MM: I started the summer after I graduated from high school. The first time I went, I didn’t have fake ID and I passed okay. But that was after several nights of walking back and forth in front of the door before going in. It was a bar called the High Room. I had a stinger, my first drink in a gay bar.

F: What’s a stinger?

MM: Stinger was made with crème de menthe and vodka, and maybe something else that’s really sweet.

F: Gross.

MM: Totally gross.

Editing this convo to a very abridged version to preface the play was challenging, to say the least; I was enthralled, and every tiny detail of the story was informative and felt important.

For the sake of getting to the point of this piece, I will loop us back to my late nights looking at digitized versions of the Village Voice, where it got weird, and link it to the period of Merril’s life in New York City when she was living in the Lower East Side (LES) in the 1960s, and how this back story of was foundational to her arrival in Tennessee years earlier. In our interview, she spoke briefly (see interview pull below) about a short-lived head shop she and her gay friends had called Paranoia. She even pulled out the pink and green business card during the interview because I showed so much immediate interest, which I’m so grateful I photographed and kept track of. It hit a cord and stuck with me; I love an obscure brick-and-mortar shop and already have a weakness for the counterculture of this period, walking a fine line between romanticizing it pretty much constantly because of my upbringing.

Merril’s stories were deep cuts because typically, we never get women-centered and, even more rarely, queer peeks into that period. So, to paint an embarrassing picture, I was basically drooling over every word she told me. But the point of our interview was to talk about Bar Dykes, not the counterculture scene in the LES during the late 60s, so I tucked it away in my memory bank until recently.

If you want to know more about how Merril ended up in NYC living in the East Village “full of artists, hippies, and freaks,” how she met Robert Patrick when he waited tables at the Caffe Cino, bought a bus from the infamous merry prankster Joey Skaggs he called his “Fuck Palace,” and ended up on their land they called “Belly Acres” in rural Tennessee. I suggest finding a copy of Bar Dykes. Beautifully designed and published by Caroline Kern of Pegacorn Press, it’s still in print, now in its 5th edition, or one of Merril’s oral histories or interviews, as mentioned earlier.

But for the sake of my late-night discovery, I thought I’d share this unpublished, extended, edited excerpt from our interview, which gives a bit more context about how I learned about Paranoia and the subsequent and equally interesting and hard-to-find information on First International Psychedelic Exposition (FIPE):

FL: You ran a head shop in the same neighborhood around this time too, right?

MM: The head shop was called Paranoia, and we sold only handmade crafts made by people in the neighborhood. Then, we had a free kitchen with food, vegetables, and grain, stews. All of First Avenue was Italian vegetable stands. So we go through the garbage and get all the good trimmings that they cut off everything. Every day, we would go down to Greenberg’s, the health food store, purchase a whole bunch of grains and beans, throw them in this great big pot, and cook everything together. And then kids, homeless people, and whoever wanted would come in and eat. It was really sweet. It was the flower summer of 1966. There were tons and tons and tons of young homeless hippie kids on the streets there before it got ugly.

F: What was the name of that one event you guys were invited to do?

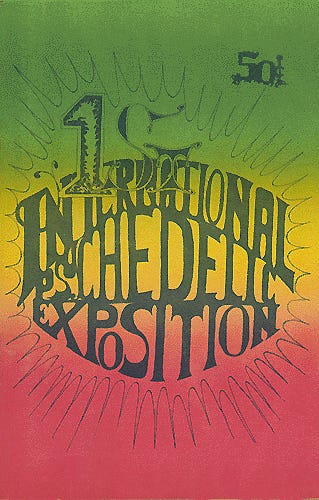

MM: The First International Psychedelic Exposition. Yeah. And you know, I wrote a piece about that, and I think I might have -- did I come across somewhere? It was in -- Paul Krassner. You know Paul Krassner?

F: I looked this up at one point and couldn’t find where it would have been. He was a critic, right?

MM: No, he used to write for the Village Voice back in the days when Jill Johnston was coming out in the pages of the Village Voice. These are all really old people whose names aren’t around anymore….We [Joey Skaggs, Robert Wilson, Jerry Robbins] were all kind of kids on the street together kind of thing.

F: How long did the head shop Paranoia last? What did it look like inside?

MM: Oh my gosh, it wasn’t even a year. It was just maybe six or eight months. There was a day-glow carousel room with kid’s carousel horses and a hand painted tin ceiling.

F: How long did it take to paint the ceiling?

MM: It took 100 hours, with three of us, so 300 hours. It was a gorgeous ceiling. We put ads in the Village Voice and the bulletin board section following our progress: Paranoia, Wait Until You See the Ceiling. Paranoia, What Do You Think It Means? Stuff like that. Then we had a grand opening, Paranoia, It’s Opening, with the time and the date.

F: Wow, that is so cool. Was there a party for the opening?

MM: Oh sure, yeah. Big party.

F: How long did you actually live in New York?

MM: Ten Years. We’d been there a long time, and it was getting heavy. While we were at the First International Psychedelic Exposition, we had a wonderful evening in the sauna room, where everybody was tripping and stoned. We were talking about people’s plans to leave the city and go back to the land. We had a bunch of friends who went to live at the Hog Farm out in New Mexico with Wavy Gravy. They were the ones who had cleaned up after Woodstock, and that was a lot of fun. We thought we’d probably join them there. It was a couple of years after that that we left.

F: Wow, I didn’t know you went to Woodstock.

MM: Yeah, we went to Woodstock. We managed to get as close as two miles from the stage. It took six weeks to get there. It was the biggest party parking lot traffic scene…

Merril explains more about their time at Woodstock before discussing the directionless trip that landed them eventually in Tennessee. Basically, she was at the center of it. In 2016, I couldn’t find Krassner’s book online; the one Merril mentioned she wrote a piece in. Now, it’s online thanks to the wonderful and important resource, the Internet Archive, which allowed me to peruse the text without purchasing. Published in 2001 by High Times, Psychedelic Trips for the Mind is summarized on Goodreads as including “funny, wild, and illuminating tales by and about such mind-altered luminaries as Timothy Leary, John Lennon, Abbie Hoffman, Groucho Marx, Jerry Garcia, Eldridge Cleaver, Squeaky Fromme, Wavy Gravy, Ken Kesey, Ram Dass, and even Hollywood's "million-dollar mermaid" Esther Williams, among many others.” The little information available online about the FIPE offered conflicting information, but this valuable 2005 article, Krsna Culture in Music, by Jahnava Devi, shared both the cover and interior copy from the 4-page exhibition catalog, listing an impressive roll call of exhibitors, including “the Psychedelicatessen head shop, Paranoia,” and described the programming as:

The purposes of the First International Psychedelic Exposition are manifold. On one level we hope to give the general public a glimpse of the psychedelic world and the beautiful creations it has inspired. On another level we hope that open and forthright exposition of psychedelic phenomena by the people it has inspired will facilitate communication between those who are somewhat fearful of the mind expansion experience and those who have had the experience and found a method to present what they found most worthwhile, be it through music, art, visual techniques, or group events." The catalog also promoted "a common drug available to anyone with $5.00 to spare - lysergic acid diethylamide.

Merril’s essay, “The First International Psychedelic Exposition,” is in the first chapter of Krassner’s book called “Countercultural History” and is credited as an excerpt from an unpublished manuscript, The Acid Years (I need to ask about this). It gives a first-person (lesbian) experience of an under-documented happening of this period. She sets the “van-load of laughing, colorful beaded hippies” up by explaining how they were on their way to set up a “sort of historical village of hippiedom” at the unlikely location of the happening, the Forest Hills Country Club. (Note: there are three different locations credited on the only information I can find about the FIPE, which honestly feels appropriate.)

My two cohorts and I had a store in New York City’s East Village. It was called Paranoia…One afternoon, this dude I had seen before at IFIF [International Federation for Internal Freedom] meetings and at the Paradox [macrobiotic restaurant] came strolling into the store, check out the items on the shelves, then moved in on the three of us where we sat behind the counter. “I’ll get right to the point,” he said….My partners and I are doing a psychedelic exposition—sort of like a World’s Fair of the hippie culture. Most of the other shops here in the East Village are gonna have exhibits, plus some folks from uptown and the West Side, and we were hoping you guys from Paranoia would join us.

“Only one of us is a guy,” Maria Interjected.

Dennis continued without batting an eyelash…”The idea is to make the place look like a hippie village. We draw tourists from Long Island—the hip rich folks who come to the East Village to go slumming and have an adventure—and we give them a little atmosphere, sell our product, and have fun.”

Merril goes on to explain the event in detail, confirming that “enormous crowds of straight people showed up” and that she had never seen so many hippies outside of Central Park. If this interests you, I encourage you to read the short piece yourself. You may even want to buy the book; there is a plethora of secondhand copies available. I just wanted to connect this obscure event to Merril’s short-lived headshop, Paranoia, run by self-identified gays and lesbians, to this place and time. Then to my 2016 interview in Tennessee, and finally, my late-night Village Voice paper reading in 2025.

That’s it. So many tiny crumbs to lead you to this non-point, like everything I can’t help myself from doing. If I had all the time in the world, I would write a book about the Bulletin Board; feel free to take that idea and thank me in the credits or hire me as a researcher. It’s important to mention that there are endless other amazing things about Merril. She also has this beautiful wedding footage from 1968 shot on 16mm film, which was turned into an experimental film. I had the honor of screening in 2017 in Milwaukee thanks to the visionary wonder of another gay elder Carl Bogner (whose life is being celebrated this weekend. We love you, Carl). I screened this unfinished film under title Mushroom/Haze Wedding: The Queering of a Ritual (1968, USA, 16mm transferred to video, color, sound, 25 min., work-in-progress) described as:

Photo animator & cinematographer Francis Lee’s lush, trippy documentation and evocation of the 1968 wedding of two young gay NYC teachers, lesbian Merril Mushroom and faerie Gabby Haze, who married in order to adopt children. Members of the fantastical queer East Village psychedelic crowd written up as “the illicit LSD group” by Princeton psychologist Stevens Newell et al., Merril and Gabby borrowed Newell’s estate for their weekend-long wedding “trip” and invited all their East Village friends. Lee just happened to be staying in Newell’s house. Captivated by the wild wedding costumes and the spirit of the event, he pulled out a 16mm camera and the little film stock he had with him and began to shoot. The more he shot, the more he wanted to shoot, but he soon ran out of film. To supplement the documentary footage, he persuaded the couple and their guests to return to the estate in November, re-enact some of the wedding events (including dips in the by-then frigid waterfall) and give him personal photos to use for photoanimation. Lee’s friend Baba Ram Dass narrates. The result--Lee’s wedding present to Merril and John--is slightly-faded time in a can of 16mm film.

To wrap this up, it’s worth mentioning that since Kern published Bar Dykes, it’s entered numerous library collections (DIY, public, museum, and higher education,) has been included in class syllabi, and has been performed multiple times around the country. Most recently, and maybe most importantly, in front of Merril for the first time along with her peers (as told to me by various folks who went) in middle rural Tennessee just last month. As crushed as I was not to be able to make the trip, I feel pleased to have some part of this story to share and so lucky to have not only crossed paths with but spent deep time with someone who I consider legendary in my lineage of radical women. Merril’s herstory (as she would say) is what I’m here for.

"Sometimes, when I can’t sleep and know I can’t do anything focused, I look at old digitized magazines and newspapers.” Yes, yes - this 1000x. One of the ways I've gotten through the last few months is to tediously upload the entire 80+ issue run of a nearly totally forgotten DC 70s underground paper to the Internet Archive. It's underrated as a form of therapy / self-soothing.

I self-soothe by looking at digitized old magazines. Village Voice is one I am going to add to the rotation!