More and more Alice,

but less and less Wonderland.

“Many adults have the strange notion that children’s books are created solely as bedtime stories, materials to put children to sleep. Well, I want to wake them up.” Harlin Quist, Los Angeles Times, 1974

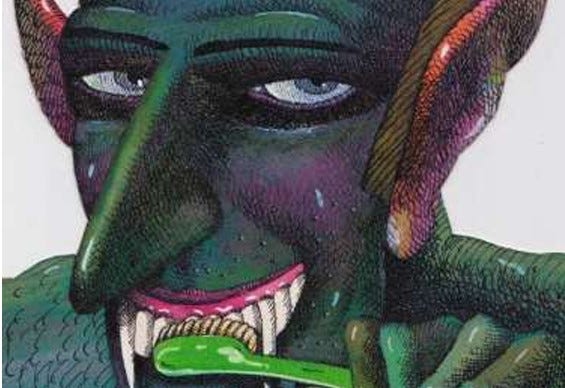

Typically, I browse the children's section at any thrift shop or used book store first. I am looking for something that I know when I see it. I’m not worried about the book's condition, but I will give it a sniff for mold or, even worse, the haunting smell of chemical-perfumed room scents. Strange, dark, radical, or unusual illustrations are the number one bait; give me a book that may lead me to something new. And, sometimes, deep nostalgia is all it takes. A beloved paperback with my favorite illustration in good shape, forget about it; it’s coming home and getting gifted to someone. You can still find a great picture book or mass-market paperback with an incredible cover for under a few dollars. Children’s books are the holdout, often still a steal compared to second-hand bric-a-brac or clothes.

Over a few visits to my favorite local used bookshop, shelved throughout various sections of the store (relevant later), I’ve accumulated a small stack of books I’ve been sitting on and waiting to write about. When I found them, I got that high of finding something special, exciting, and new (to me). I immediately started searching for more information. This was over a year ago. And I just need to tell you about them because I don’t have the focus or time to get all the answers I want or need. Maybe that will come later, to me or someone else.

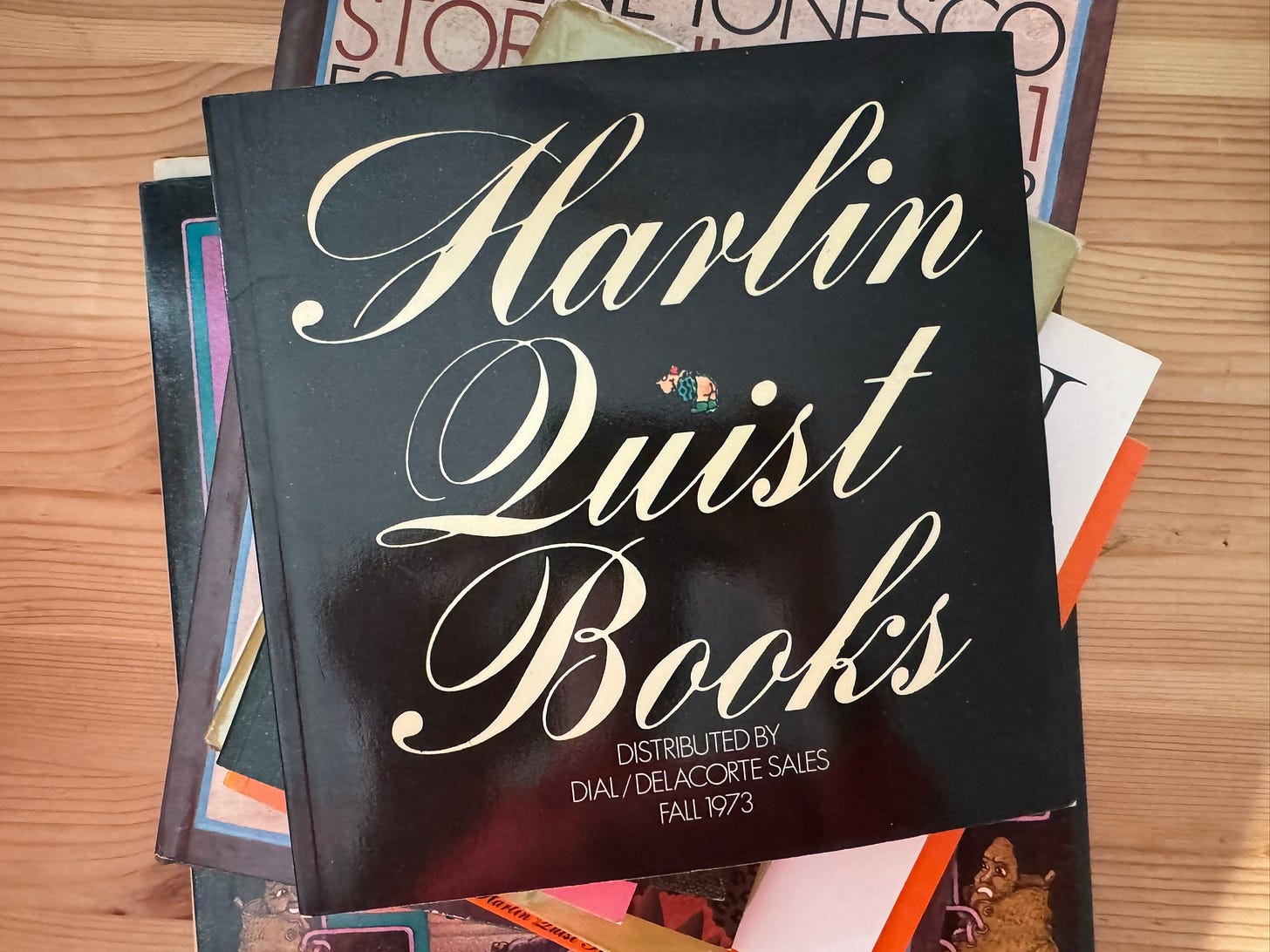

As much as I like to think I’m in the know with things in the margins and strange, it’s exciting to find something I know nothing about while I’m out in the world and not through social media or an article. This isn’t unusual for me since I’m actively looking, but I want to name it as a reminder. I never want to stop actively looking. So when I picked up one of the books, clocked the illustration style, and looked at the publisher, I noted that Harlin Quist wasn’t on my radar. Then I found another and another. And then a 1973 Harlin Quist catalog. This was all before getting home to the internet. One of the best/worst things about this bookstore is that there is no cell reception, so you can’t look things up inside, outside, or even once you’ve started down the windy road that gets you there. So you can bring a book list (yes, I have one) or not, but no quick internet searches for authors, prices, or titles you can’t remember. For me, that’s everything these days. Yes, this bookstore is in the woods, and it is magic.

A light internet search led me in a few directions. One valuable source was the 1989 article, Why the Books of Harlin Quist Disappeared—Or Did They? by Nicholas Paley. Annoyingly, behind a paywall, I reached out to Paley, who was incredibly quick to respond and excited that I was looking into his old friend and colleague, Harlin Quist. He didn’t have the article saved but mentioned that I should find his University of Wisconsin 1984 dissertation, First Encounters with the Avant-garde: Children Respond to the Books of Harlin Quist. Thanks to a professor friend, I got a PDF of the 1989 article, but the dissertation has turned into a more extended search with various librarians trying to help, but still no dice. The barriers of academia will forever irritate me like nothing else. This was part of why I was waiting to tell this story or the excuse I was telling myself, but maybe it would be a part two at some point.

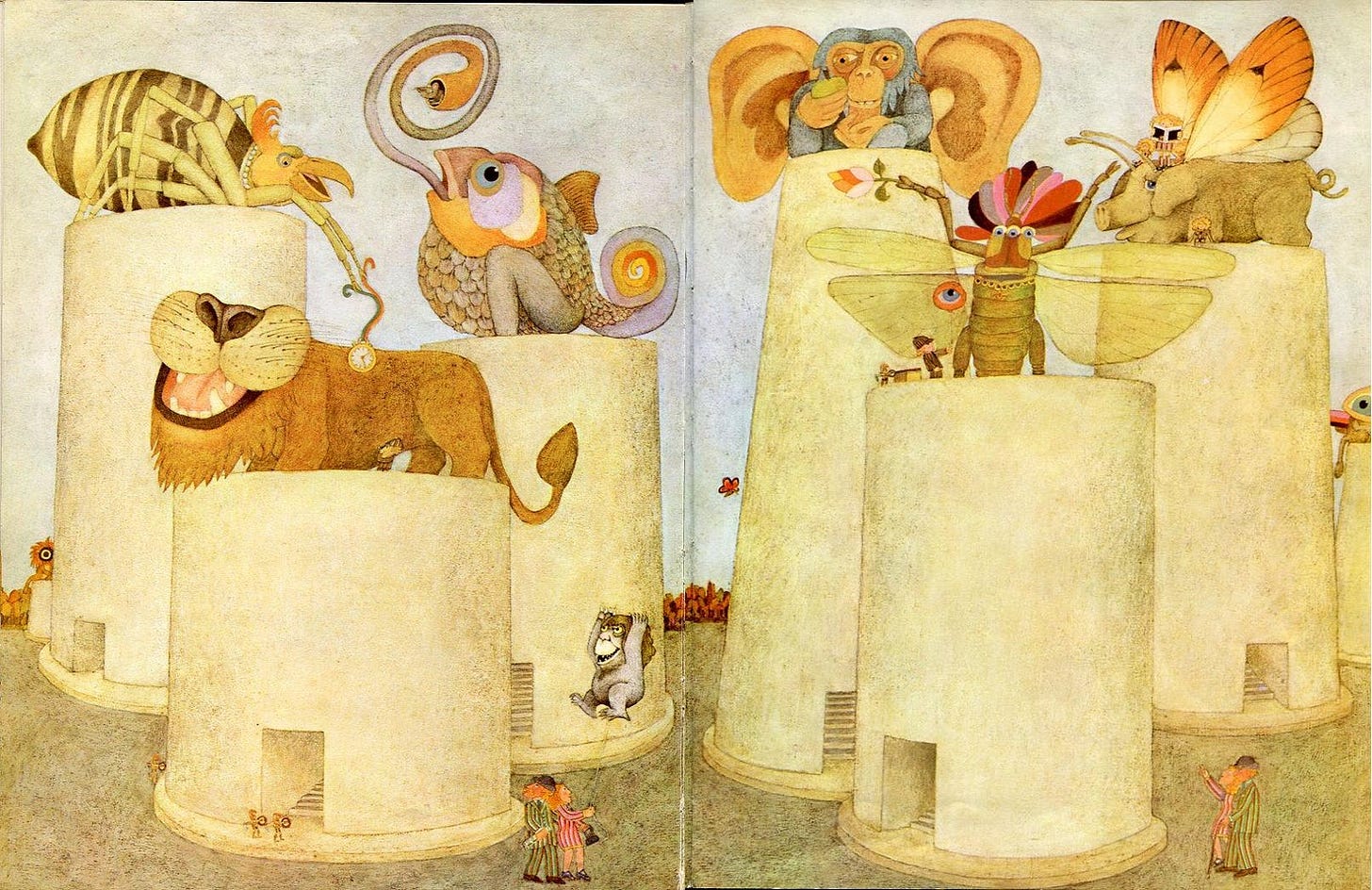

I want to avoid a biographical narrative, but for some context, Harlin Quist started his children’s book publishing career in the early 1960s. It wasn’t until 1965 that he went out on his own with “an intent to publish an artistically valuable, intelligent, progressive-even aggressive- literature for children.”1 Within five years, he had published over 70 titles, “Quist books tended to be either highly acclaimed or unequivocally censured.”2 Not surprisingly, the books gained respect in the graphic art community for their “elegant design, superb craftwork, and exquisite production.” It only takes looking at a few different titles to realize how radical and far out they were for their time in design and content. Paley goes on to say, “Quist books were repeatedly nominated to numerous national and international book award and best-illustrated book lists,” all outlined in detail within the article appendix. Accolades mentioned in Quist’s New York Times obituary included ''The Geranium on the Windowsill Just Died but Teacher You Went Right On,'' written and illustrated by Albert Cullum, sold over a half-million copies worldwide and a new French edition appeared in 1999. ''Story Number 1,'' by Eugene Ionesco, illustrated by Etienne Delessert, was a 1968 New York Times Best Illustrated Book.” The obit also mentioned in 1997, “the Salon du Livre de Jeunesse in Paris held a retrospective of original art and first editions of Mr. Quist's books in French and English that attracted 150,000 visitors.”

We Too Were Children, Mr. Barrie, a blog focusing on children’s books written by “adult” authors, reviews a handful of Quist books, including the aforementioned Story Number 1 by Eugene Ionesco. If you want to dive deep into this single title, this is the place to do it. A self-proclaimed “maniac in terms of quality,” Harlin Quist was described in a 1978 Chicago Tribue article as a man who did everything himself from “finding printers and binderies, discovering new young painting talent, commissioning books, hunting up established authors who might have an interest in turning out a child’s book.” Robert Graves, Shirley Jackson, Richard Hughes, and Mark Van Doren were in the first Harlin Quist catalog. In 1974, Digby Diehl for the Los Angeles Times reported, "Although not well known in the United States, Harlin Quist’s books have been published for the past 10 years to increasingly noisy acclaim in Europe…. Published simultaneously in eight languages and distributed in this country by Dial/Delacorte, Harlin Quists’s visually brilliant Fantasy-oriented materials are exciting forays into often uncharted areas, and for this reason they have frequently offended the Children’s Book Establishment.”

In a much earlier 1967 Chicago Tribune article, A New Publisher with Many Ideas, Quist is quoted, “I published one book written by two 13-year-old girls who’d been trying for two years to sell it to every major publisher, only to have the door slammed. When they were 16, they brought it to me, and it became an absolute sleeper. It’s ‘Hubert, the Caterpillar Who Thought He Was a Mustache,’ and one department store, which ordered 10 or 12 copies, had none for its shelves because every clerk bought one to take home.” Now, I have to sequester the urge to see if the two authors are still alive and ask about their memories of that experience. WTF, A potential part 3 of this story?

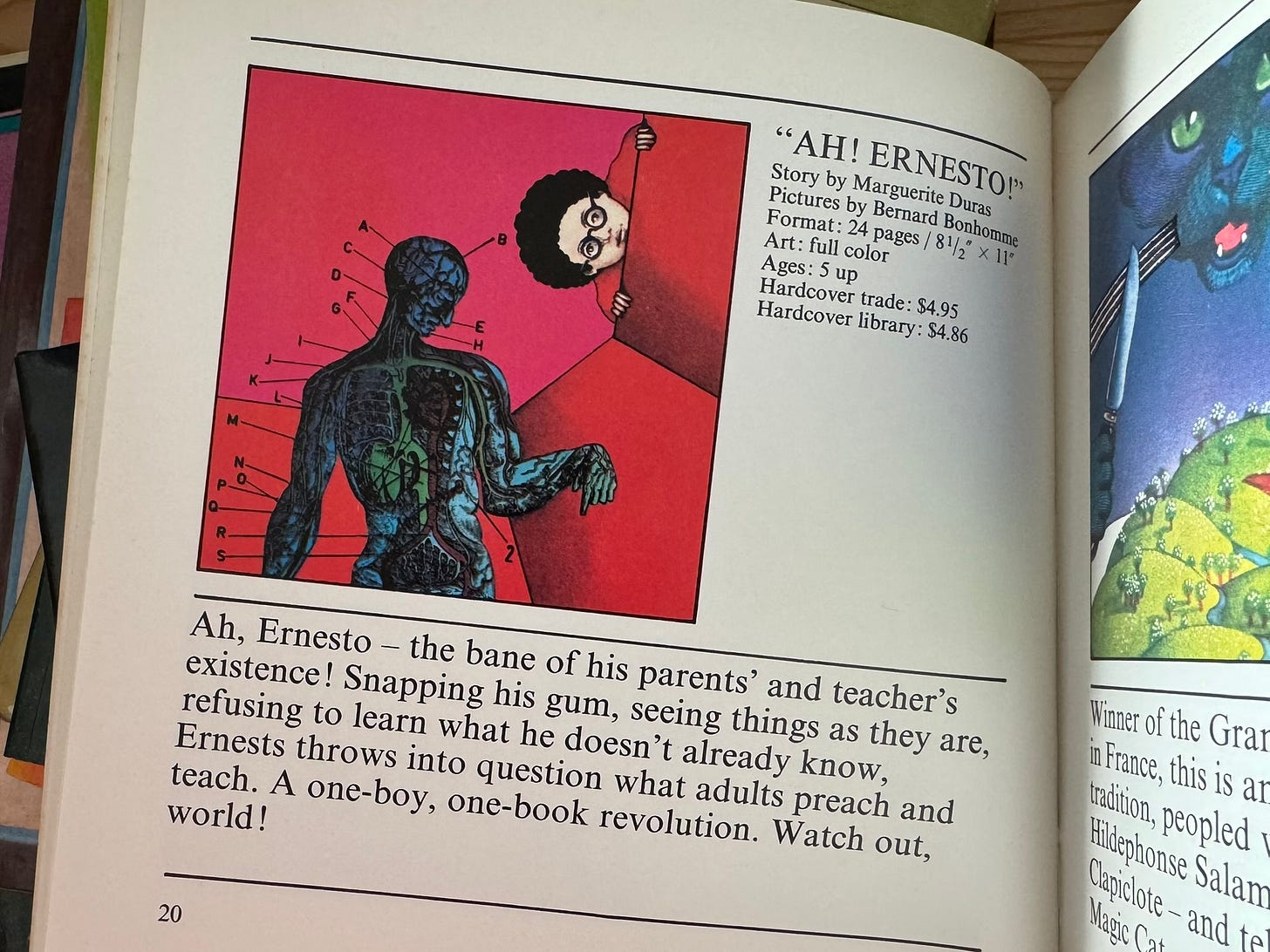

In the late 60s, children’s books became a part of the counterculture. They were folded into the racialization of the times. In her expansive 1998 paper exploring this topic, Sophie Howard says, “The question of institutions and education policy was an adult affair. Yet children’s media and culture was also very much engaged in the questioning of schools. In the picturebook Ah! Ernesto, published by the Franco-American duo Harlin Quist-Ruy-Vidal Marguerite Duras offered children an excoriating critique of the school system, in which young pupil Ernesto is likened to a butterfly pinned to the classroom wall: “it’s a crime.”3

Snapping his gum, seeing things as they are, refusing to learn what he doesn’t already know, Ernests throws into question what adults preach and teach. A one-boy, one-book revolution. What out, world!

Paley echos this sediment from a decade earlier, “In retrospect and from the vantage point of the late 1980s, perhaps Quist books can be best understood as part of the larger, remarkable social, cultural, political, and artistic upheaval in American society that took place in the 1960s in which established views were vigorously challenged and inventively rearticulated from a variety of perspectives. The iconoclastic nature of Quist books provides unique evidence of this resistance to and reconceptualization of traditional forms of institutional power.”4

There are about a million relatable things that Harlin Quist is quoted saying or reported on doing. I’ve barely scratched the surface with the incredible catalog of illustrators and authors he collaborated with. Start searching. The slippery slope is avoiding the impulse to collect the entire Harlin Quist catalog, so ultimately, I need to save myself from that. I like to think that if we worked in the same decades, we would be friends, and imagine I would send artist friends his way that I know he would like. He feels like kin or someone who laid the path for many things I appreciate and enjoy. A small publisher who started with no money, never married, and liked weird, beautiful, nonsensical things made by established authors and children alike. A guy so skeptical of the American publishing industry that in a 1967 piece commissioned by GRAPHIS 131 (an issue entirely dedicated to “artistically valuable children’s books”), Quist wrote;

A so great number of books are published. And Great numbers are sold. The publisher earns his profit. The editors congratulate one another on an occasional book of distinction. The buyers–for the most part, parents and librarians–buy the best of what they are presented. And the children are offered–well, that question again: what are they offered? One opinion: ‘More and more Alice, but less and less Wonderland.’

But within all the bits I found on his life, the thing that most resonates with me is how he said he had no trouble finding publishable material or ideas for authors to turn into books. “Ideas are no problem, tho capital is.” FOR REAL Quist, I feel you.

Tell me your Harlin Quist stories. How was I so late to the game?

Paley, Nicholas. "Why the Books of Harlin Quist Disappeared—Or Did They?" Children's Literature Association Quarterly 14, no. 3 (1989): 111-114. .

Ibid.

Sophie Heywood. “Children’s 68: introduction“ Open Edition Journals.

Paley, Nicholas. "Why the Books of Harlin Quist Disappeared—Or Did They?"

I just read Didion and Babitz and learned that Eve's last book was an imprint about an Italian fashion house published by.... Harlin Quist.

love this - thank you for this introduction to Harlin Quist