The Back Story

I’ve been in Provincetown for the past week at a self-directed Fine Arts Work Center residency. Last fall, I had the foresight and privilege to book this time for myself, knowing I would need dedicated headspace to flesh out the details for an upcoming exhibition I am curating in November. It’s an extension of my research from As Ever, Miriam (2024), which coincidentally had the second edition released this week via my new publisher, Combos Press.

I’m always slightly distracted by local history. I knew staying focused while in town would be extra challenging because Helen Hoppin, an early student of Charlotte Partridge and Miriam Frink (the subjects of my research and exhibition), spent time here in 1923 as a part of the infamous art community studying under William Zorach.1 I’ve been low-key obsessed with Hoppin since I learned about her a few years ago for reasons I’ll share in the future. She has her own robust research file that I’ve built up, knowing she will be woven into a contemporary conversation about their networks, community impact, and her prolific short career.

So, of course, I walked past the addresses I knew Hoppin wrote letters from, blocks from where I was staying, and made an appointment with archivist Nan Cinnater at the public library.2 My meeting didn’t manifest any new information about Hoppin, but did allow me to spend some time in the building, an incredible space and local resource. Talking with Nan, who has lived in Provincetown for 30 years and shares a lot of my interests, was fantastic. I also left some information about Hoppin, so she could contact me later if anything surfaced.

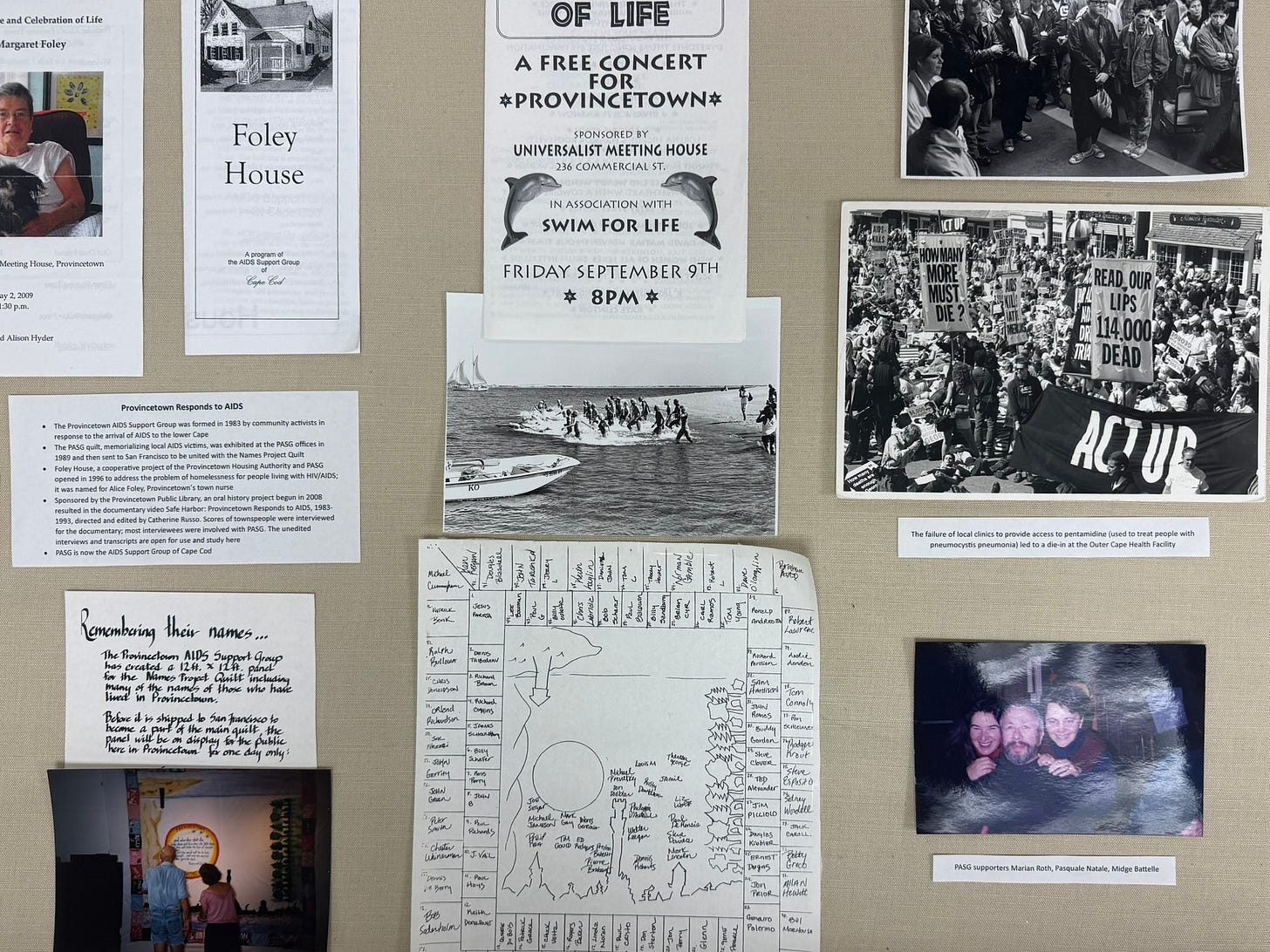

While wandering around the library looking at the art collection, displays, and the giant ship I came across a display case tucked in the basement (hot tip: the library has a great used book space down there) with a small selection of about twenty pieces of archival materials: photos, flyers, notes and minimal didacts about the history of the early (1983) response to AIDS in Provincetown. I didn’t know any specifics about this important and radical history, but as a gay mecca, it makes sense. Based on the minimal labels, I wanted to know more and started doing light online searching. The history is well documented, and I won’t spend time rehashing it here except to give you a few resources if you are interested. The Provincetown History Preservation Project hosts the Safe Harbor/AIDS Archive Collection that has a wide variety of ephemera and articles “related to the making of the Safe Harbor documentary directed by Catherine Russo, a 22-minute video produced from many interviews with Provincetown AIDS survivors and community caregivers.” I couldn’t find an active link to the documentary anywhere to watch it. The collection is housed at the Provincetown Public Library, and I would assume the source for the displayed materials; however, they are not digitized on the website.

I highly recommend reading Masha Gessen's 2018 critique in the New Yorker, What the Provincetown AIDS Memorial Leaves Out, which provides a lot of context and spot-on critical history, and the equally informative uncredited piece from 2022, Rising to the Moment: Lesbians and the AIDS Epidemic in Ptown.

All memorials smooth over history, leaving out much of the passion, the tragedy, and, most of all, the stories of the victims. (The two-hundred-and-fifty-foot Pilgrim Monument that towers over Provincetown, indeed almost directly over the new AIDS memorial, is a study in omissions.) The AIDS monument, too, is remarkable for what it omits. The phrase “open community” subsumes the word “gay,” and it also elides why people with AIDS came to Provincetown seeking help. They came because they had no place to go. They came because their own parents wouldn’t touch them, and neither would their doctors and nurses, who put on gloves and, sometimes, hazmat suits before entering the room of an AIDS patient. -Masha Gessen

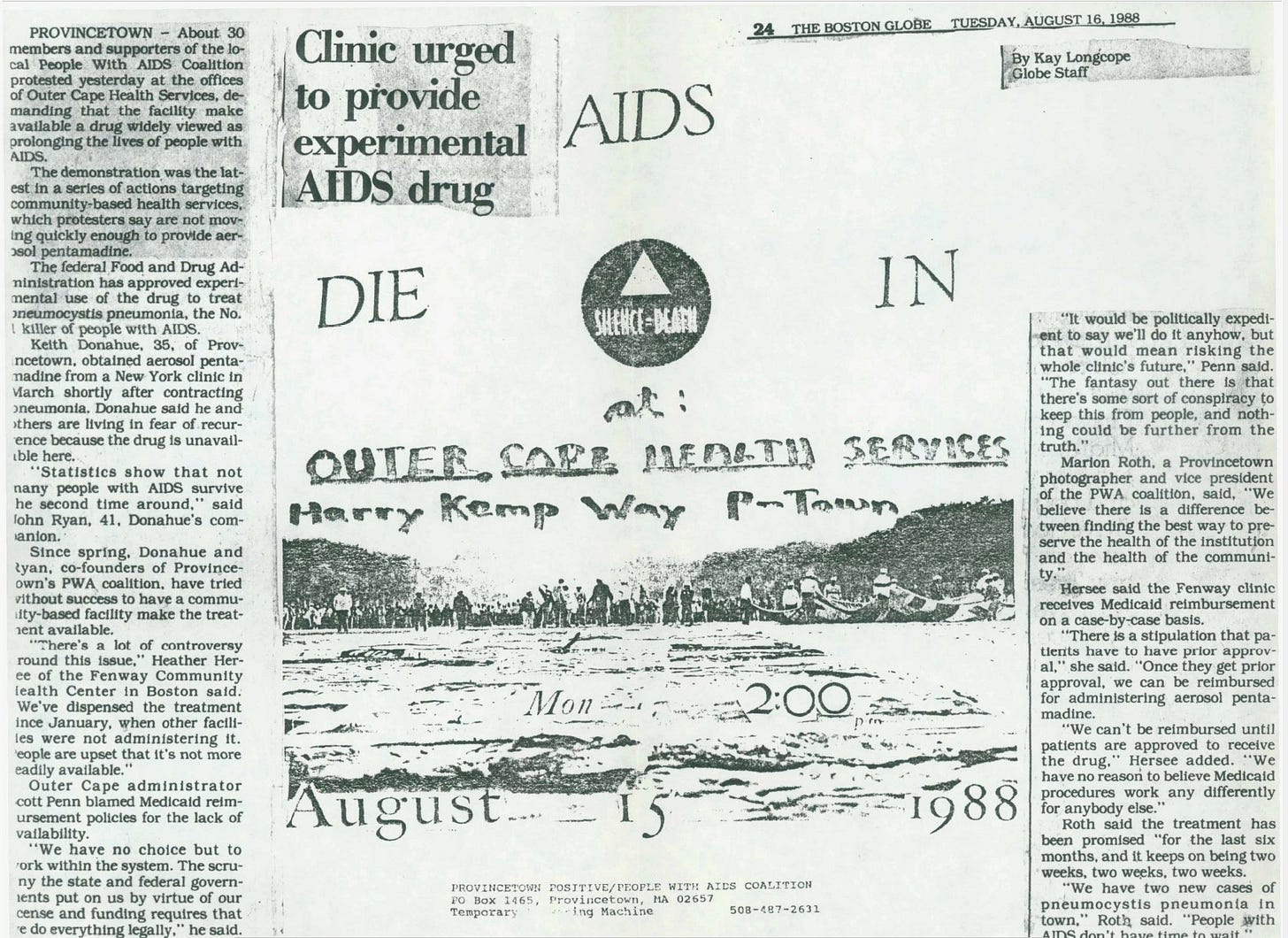

The DIE-IN: Outer Cape Health Services 1988

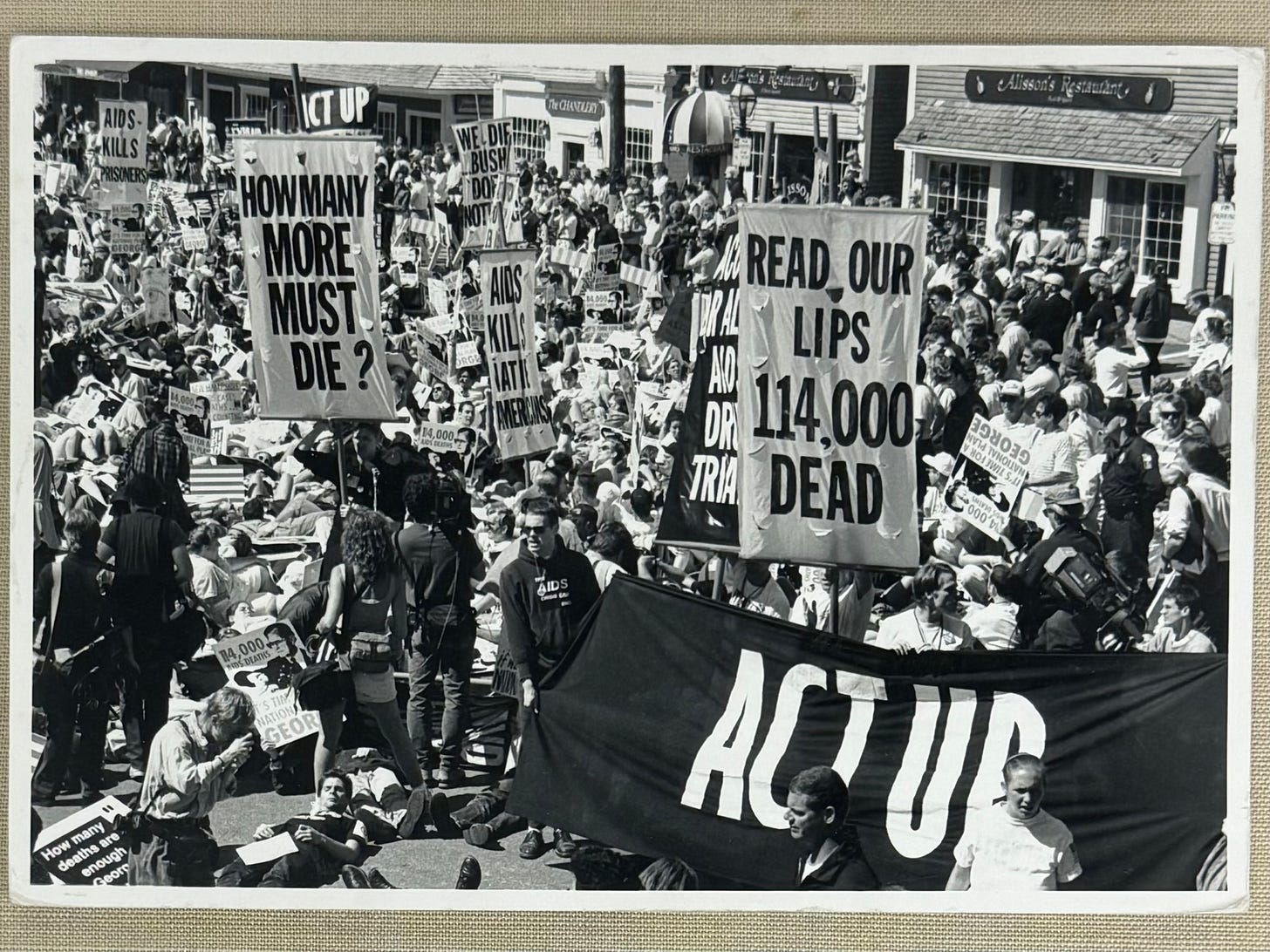

I locked in on two things in the display case: the ACT UP DIE-IN protest photograph I used at the top of this post and the sketch for the AIDS Memorial Quilt. Having been invested in ACT UP’s activism tactics since I was a teenager, I wanted more information about ACT UP’s presence in Provincetown.3 I spent about an hour trying to figure out more information about the DIE-IN protest and the source of the image, and discovered a few things. The image above is digitized in the collection and gives a date and the year for the Provincetown DIE-IN. It appears to be a cut-and-paste Xerox of an article from The Boston Globe published the day after the DIE-IN was scheduled, pasted around the flyer for the protest, with no other information offered. I would assume this was kept as a part of someone’s scrapbook to document the events surrounding the epidemic.

The Provincetown action isn’t listed on the ACT UP timeline. I also looked closer at the photo and searched for Allison's Restaurant, clearly visible in the background, and confirmed this image is actually from Kennebunkport, ME. Likely from the infamous action where “Amid extraordinary security for the vacationing President Bush, some 1,500 demonstrators marched noisily but peacefully through this resort town Sunday, demanding more action on the AIDS crisis. marched noisily but peacefully through this resort town on Sunday, demanding more action on the AIDS crisis.”4 The protest ended in a DIE-IN in downtown Kennebunkport, which aligns with this photo. It seems likely that someone in Provincetown traveled to the protest, resulting in this document ending up in the collection, but that is just speculation.

The photograph in the case at the library is unintentionally misleading with its caption, “The failure of local clinics to provide access to pentamidine (used to treat people with pneumocystis pneumonia) led to a DIE-IN at the Outer Cape Health Facility.” We know from the archived flyer that a DIE-IN did occur, but this image is not from that specific action. Since it can be deduced that not all the materials in the archive have been digitized, this could be an interesting space for someone to step in and see what else has been preserved regionally from ACT UP’s incredible and robust history. Not my project, but I would love to see the result of this inquiry.

The Quilt: Remembering Their Names

“Before it is shipped to San Francisco to become a part of the main quilt, the panel will be on display for the public here in Provincetown for one day only.”

The sketch from the Provincetown panel of the AIDS Memorial Quilt felt intimate, like seeing a draft of a heartbreaking love letter. I have never had the opportunity to see any parts of the quilt in person, but I have strong memories of being in elementary school and first hearing about it, and it’s followed me around as an example of craft activism my entire life. Considered “the largest community art project in history,” the first panel was made in 1989, with 44 names, expanding every few years with additional rings now it “contains the names of 113 people who died in Provincetown between 1983 and 1992 — starting with Glenn, a man who came from Boston in 1982 and died so quickly that the nurse who cared for him, Alice Foley, wasn’t able to get his last name.”5 The glossy 4x6 photo next to the sketch seems to be documentation of the single day it was viewable in 1989. The quilt panel last returned to Provincetown in 2024.6

There is a place for you in this movement.

Gessen wrote, “They came because they had no place to go” and this can be said for generations of queers who to came to Provincetown for various of reasons. Helen Hoppin came to paint and lean into non-traditional ways of being a woman artist in the 1920s. The gruesome reality of why gay men came to Provincetown during the AIDS crisis is much less romantic, yet exemplifies, as remembered in the archive, acts of radical resistance, memory, and care.

May we all learn from our mentors, queer elders and ancestors and be on the right side of history. In the powerful words of queer Mexican artist Leo Herrera,7

AIDS activism took many forms. Some threw their bodies against riot shields and staged protests which dazzled with fury. Others photographed the giant bodies of their lovers, sewed grief into a quilt, used words and brushes like a scalpel. Our front line pioneered harm reduction and treatment, revolutionizing medicine. We organized, donated, and mobilized voters. We educated our mothers.

There is a place for you in this movement. Let the powerlessness wash over you, allow yourself time to grieve, then get to work. Only you can figure out what you can bring to this moment. 9.25.20

Shout out to his wife Margutrite.

This was a last-minute decision, and Nan was eager and available to meet on short notice. There are other local resources I didn’t tap into, but if I have time and resources in the future, I will. Future Ptown planning is swirling…

The Pink Triangle That Mobilized a Movement: The iconic protest visual used by SILENCE=DEATH and ACT UP became a key symbol of AIDS activism and LGBTQ+ advocacy, by Maya Pontone, Hyperallergic.com, June 9, 2025

AIDS Protest Brings Issue to Bush’s Door : Demonstration: Beefed-up security in Kennebunkport assures distance between activists, President. Police guards wearing gloves are jeered, Associated Press, Los Angeles Times, September 2, 1991.

After 10 Years, AIDS Quilt Panels Return to Provincetown, by Paul Benson, The Provincetown Independent, June 19, 2024.

Ibid.